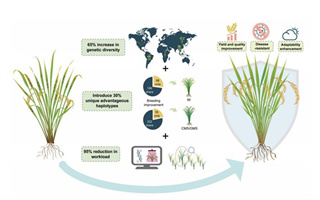

植物育种,作为一门历史悠久且关键的学科,长期以来被视为“科学与艺术的结合”。然而,在短周期作物(如玉米、小麦、水稻)为代表的现代育种中,这一传统的浪漫化描述正被彻底改写。现代数据驱动的育种方式挑战了“艺术”的地位,改变了以往依赖直觉和经验的育种方法,将“艺术”还原为可量化、可预测的科学,并使育种过程变得更加系统化与工程化。

时代的变迁:从“少数地块”到“数千个地块”

传统“育种家眼睛”的历史背景

传统上,育种家的视觉判断在育种工作中至关重要,尤其是在早期阶段的视觉筛选(1960年代)。在育种项目初期,种质资源高度多样化(如绿色革命时期的水稻),面对几十到几百个地块,育种家依靠眼睛和经验来挑选出表现优异的植株。

现代育种的挑战

然而,现代育种项目,如工业化生产纯系(如DH或RGA),涉及数千个产量试验地块。在这种规模下,主要性状(如成熟期、株高)趋于一致,视觉评估变得几乎不可能。为了在数千个地块中选择最佳品种,育种家需要更高精度的数据支持——例如,区分50克产量差异,纯靠眼力已无法胜任。

现代育种:从“艺术直觉”到“数据洞察”

数据驱动的育种方式

“数据至上”并不意味着育种家可以待在办公室里或待在实验室只靠模拟育种,相反,它重新定义了育种家与田地的互动方式。现代育种家已经从依赖经验直觉的“艺术”转向了通过数据和统计分析作出决策的“科学”。

过去所谓的“育种直觉”,实际上是育种家多年积累的经验,能够对数据进行高级模式识别,在十年如一日,南繁北育,刻意练习的结果。现代技术,如基因组学、数据分析和传感器,可以将这些模式显性化、可测试化和可规模化,将“直觉”转化为有数据支持的决策。

现代育种的田间观察

现代育种家的田间观察,不再是单纯寻找“大穗子”或“大玉米棒”,而是带着统计学和数量遗传学的视角:

监控非遗传效应:重点观察对照组的长势,判断是否存在空间趋势,如不均匀的灌溉、施肥或病害。

排除干扰数据:识别并记录因管理不善等导致的不适用地块、行或区组,在数据分析中排除。

补充数据分析:确认区组效应,验证空间矫正模型的合理性,确保非遗传效应被最小化。

决策的算法化和可复现性

现代育种流程中的选择是基于可量化、可预测的模型进行的,而非个人“直觉”。如果两名育种家拥有相同的环境、表型和基因型数据集及相同的模型,他们将做出相同的选择。

现代育种的核心:系统工程与可预测的遗传增益

现代精英育种的本质是一套工程化、可量化管理的流程。育种的目标是优化作物性能,而不是单纯的表现形式。通过使用BLUPs、GBLUP、机器学习~和环境协变量等工具,育种家能够实现系统化、可预测的遗传增益。自动化和标准化的流程正在逐步取代个体的“匠人精神”。

因此,现代植物育种更应被视为一门严谨的数据科学与系统工程,旨在通过量化、可复现的方法,优化和预测农作物的改良。

智种评论

这篇文章为国内育种界提供了非常直接、现实的提醒:现代育种已经不再是“师傅带徒弟”的经验艺术,而是扎扎实实的定量科学与系统工程。

在今天的大规模、多环境和强竞争的育种体系中,单纯依赖“眼力”和“直觉”已经无法支撑持续的遗传进步。真正能够拉开差距的是对数量遗传学、统计建模、基因组预测、试验设计、数据清洗与空间校正等现代工具的掌握能力。

对育种从业者的几点建议:

田里不能少走,但眼睛要变成“统计学家的眼睛”:现代育种家要具备识别非遗传效应、判断试验质量和理解空间趋势的能力,而这些都需要通过数据分析来支持。

育种直觉不是“天赋”,而是长期结构化学习的产物。积累的经验固然宝贵,但需要与可量化的工具融合,才能放大效能。

现代育种已是“系统工程”,这意味着流程设计、试验布局、数据质量控制、预测模型选择,比“挑穗子”更为重要。

多读经典,回到理论本源:现代育种者应不断深化对遗传学、统计学和试验设计的理论理解,这些基础理论是将“艺术”转化为“科学”的关键。

推荐经典书籍:

Falconer《Quantitative Genetics》

Lynch & Walsh《Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits》

Bernardo《Breeding for Quantitative Traits in Plants》

Piepho《Experimental Design and Analysis for Plant Breeding》

这些书籍将帮助育种者更好地理解现代育种体系的底层逻辑,并在数据时代的竞争中站稳脚跟。这些书可能对大家读起来有些吃力,建议去读下《玉米育种学》第三版,再用AI工具去读这些经典理论,可能受益匪浅。

原文:

In a previous post, I mentioned that “Data is king; breeder’s eye is a myth.” I appreciate those who both agreed and disagreed with that statement. I feel I need to expound a bit on the context of that statement in an elite breeding program involving short-duration row crops.

- a breeding program that is just being established which might use a very diverse set of founders (e.g. 1960s green revolution rice breeding) may rely on visual phenotypic selection of breeders from F2 to field trials to select for obvious qualitative traits from a FEW DOZEN to FEW HUNDRED plots.

- an elite modern breeding program consisting of an industrialized inbred production (DH or RGA) and THOUSANDS of yield trial plots simply does not make sense for the traditional definition of a breeder’s eye. Elite crosses would mean the major traits would have been fixed, and traits such as maturity and height would be almost uniform in an elite population. Visual selection on a trait with a highly continuous variation such as yield will require a resolution of ~50 grams (good luck!). Visual evaluation of thousands of plots in several locations is virtually impossible.

The priority for early-stage trials is to make sure non-genetic effects are minimized. We can redefine the Breeder’s Eye as follows:

- Breeders should be familiar with the checks. evaluate the check plots scattered throughout the field. Vigor of check plots across large trials can give an idea of spatial trends in the field, which can be confirmed when data is analyzed.

- evaluate the range and rows (or columns and rows) and note the presence of range/row/block effects, typically cause by non-uniform irrigation, fertilizer application, disease incidence, and cultural management practices. These observations will complement data analysis.

- Take note to exclude rows, ranges, blocks or plots that are unusable in the analysis of data.

- If populations are blocked, take note of promising populations and pedigrees.

- As you go through the field prioritizing check plots, some entries may catch your attention. It is okay to spend time on those plots tp learn more about the traits, genes present, pedigree, etc. Breeders will do this plot-by-plot evaluation in late-stage trials when entries are lessMODERN, DATA-DRIVEN PLANT BREEDING IS NOT AN ART

I have posted several times on this topic, and each time there are misinterpretations. I am hoping this can be clarified here.

Plant breeding has often been described as also an “art.” Modern data-driven breeding challenges that idea not by removing something mystical, but by revealing that what we long called art was actually misunderstood science and experience.

Misconception 1: “Data-driven breeders don’t go to the field.” This is incorrect. Field observation remains central. Data-driven breeders integrate genomics, analytics, sensors, and digital workflows on top of strong field experience. However, modern breeders look at a field trial with the perspective of statistics and quantitative genetics, while traditional plant breeders look at a field trial searching for big panicles, large ears and other observable phenotypes.

Misconception 2: “Breeder intuition is art.” Not quite. What people once referred to as intuition is actually pattern recognition built from years of exposure to data, even before it was digitized. As Adam Grant explains in The Originals, intuition becomes reliable only when it emerges from repeated, structured learning. Modern tools now make those patterns visible, testable, and scalable, turning “intuition” into transparent, data-backed decision-making.

Misconception 3: “Creativity disappears in data-driven breeding.” Creativity isn’t gone, it has moved. What used to be viewed as the “art” of picking plants is now the engineering creativity of designing superior pipelines: smarter testing schemes, simulations to shape crossing blocks, optimized selection strategies, integrated phenotyping and genomic prediction. This creativity is systematic and measurable, not mystical.

The truth: Modern breeding is not an art. It is a discipline rooted in data, experimentation, and intentional design. What used to be labeled “art” was simply scientific reasoning and pattern recognition before we had the tools to quantify them.

And by the way, different crops and programs would have different stages of transitioning “art” out of breeding activities, and that is okay.WHY MODERN PLANT BREEDING IS NOT AN ART

Plant breeding in elite, data-driven pipelines is not an art because decisions are governed by quantitative genetics, reproducible analytics, and structured workflows aimed at delivering predictable genetic gain, not personal intuition or aesthetic preference.

1. Modern breeding is governed by quantifiable, predictive models, not intuition. Elite pipelines operate on statistical genetics, quantitative trait models, genomic prediction, and algorithmic selection. Decisions are made using heritabilities, GxE models, haplotype effects, and prediction accuracies, not on personal “feel” or aesthetic judgment.

2. Selection is algorithmic and reproducible. In advanced programs, if two breeders have the same datasets (phenotypes, genotypes, environmental metadata) and models, they will make the same selection decisions. Reproducibility is a hallmark of science and engineering, not art.

3. Pipelines follow structured, stage-gated workflows. Elite breeding programs run using defined breeding schemes, molecular QC and selection, stage-gate advancement criteria, multi-environment testing, decision-support tools. These are standardized engineering workflows aimed at throughput, quality control, and risk reduction, unlike the free-form nature of artistic creation.

4. Big data and analytics drive advancement decisions and may rely on BLUPs and GBLUPs, machine learning, high-throughput phenotyping, environmental covariates, and many more. None of this is interpretable as “art”; it is data science, statistics, and bioinformatics.

5. The objective is performance, not expression. Art aspires to expression, originality, or aesthetic outcomes. Breeding pipelines aim for measurable genetic gain, product delivery, predictable trait introgression, and improvement in farmer ROI.

6. Outcomes are benchmarked against objective KPIs. Breeders are held accountable for rate of genetic gain, deployment timelines, market share of products, trait delivery metrics and pipeline efficiency. These are engineering KPIs, not artistic judgments.

7. High-performing pipelines reduce individual “craftsmanship”. With automation, analytics, and standardized workflows, crossing decisions use algorithms such as optimal contribution selection and advancement relies on genomic predictions or multi-environment statistical models in later stages. The personal “touch” disappears, the system produces the gain; the individual does not “craft” varieties.

8. Complex traits require systems engineering, not artistic intuition. Yield, adaptation and trait indices involve polygenic architectures, nonlinear GxE interactions, and physiological trade-offs. These require integrated systems biology + data engineering.

9. Success is validated through external empirical testing. New varieties must outperform checks across multi-location trials, show stability, and pass regulatory benchmarks. Art is not validated against empirical performance curves; breeding is.

来源:Mark Nas等